Differential Privacy as Hypothesis Testing

December 1, 2022

Connecting the dots between Differential Privacy and attackers.

Differential Privacy (DP) Dwork, C., McSherry, F., Nissim, K., Smith, A. (2006). “Calibrating Noise to Sensitivity in Private Data Analysis”. In: Theory of Cryptography. TCC 2006 is the golden standard used both in academia and industry to reason about how private an algorithm is. In this post, I’ll give intuition on DP through an attacker’s lens, illustrating how adversaries are left with a measurable chance of leaking privacy.

Pure Differential Privacy:

Differential privacy claims that an algorithm M provides \(\epsilon\)-DP privacy if for two databases that differ in one element \(D_1\) and \(D_2\) and an output space \(O\), the following property holds:

\[P[M(D_1) \in O] < e^\epsilon * P[M(D_2) \in O]\]Dwork and Roth capture the essence of this definition in their seminal textbook:

Differential privacy describes a promise, made by a data holder, or curator, to a data subject: “You will not be affected, adversely or otherwise, by allowing your data to be used in any study or analysis, no matter what other studies, data sets, or information sources, are available."

If you did not smile, then I recommend reading an introductory material on on Differential Privacy.

In simple terms, changing one individual’s data in the dataset does not significantly alter the distribution of \(M\)’s outputs. Because of this property, an adversary who tries to pinpoint whether your data is included (or what your individual contribution might be) cannot succeed with high confidence. Next, let’s explore what adversaries actually aim to do and how Differential Privacy constrains their efforts.

Adversaries

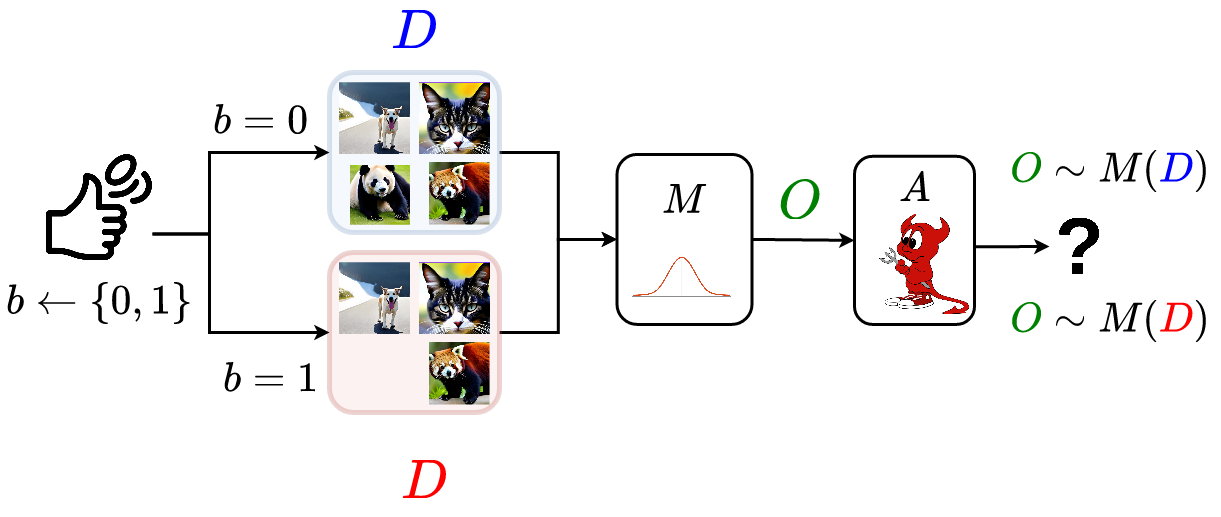

Differential privacy is the standard for data privacy because it makes no assumptions. If an algorithm \(M\) is differentially private, an attacker can have unlimited auxiliary information and unbounded computational power, yet they still cannot reliably determine whether a particular individual’s data was included in the dataset. This is due to statistical indistinguishability: the outputs of \(M\) barely change when one person’s data is swapped in or out. Moreover, DP must hold against all adversaries \(A\) and for every pair of neighboring datasets \((D_1,D)2)\). The diagram below illustrates the adversary’s objective: to distinguish whether an output came from \(D_1\) or \(D_2\).

Formally, we can view this as a hypothesis test:

\[H_0: O \sim M(D_1) \text{ vs } H_1: O \sim M(D_2)\]An “error” occurs when the adversary incorrectly guesses which dataset produced \(O\). To assess this, we look at the probability of error in a binary classification framework, where the false-positive rate (FPR) and false-negative rate (FNR) determine how successful the adversary is at telling the two datasets apart.

| True Positive (TP) | False Positive (FP) | |

|---|---|---|

| True Negative (TN) | TPR = \(\frac{TP}{TP + FN}\) | FNR = \(\frac{FN}{TP + FN}\) |

| False Negative(FN) | FPR = \(\frac{FP}{TN + FP}\) | TNR = \(\frac{TN}{TN + FP}\) |

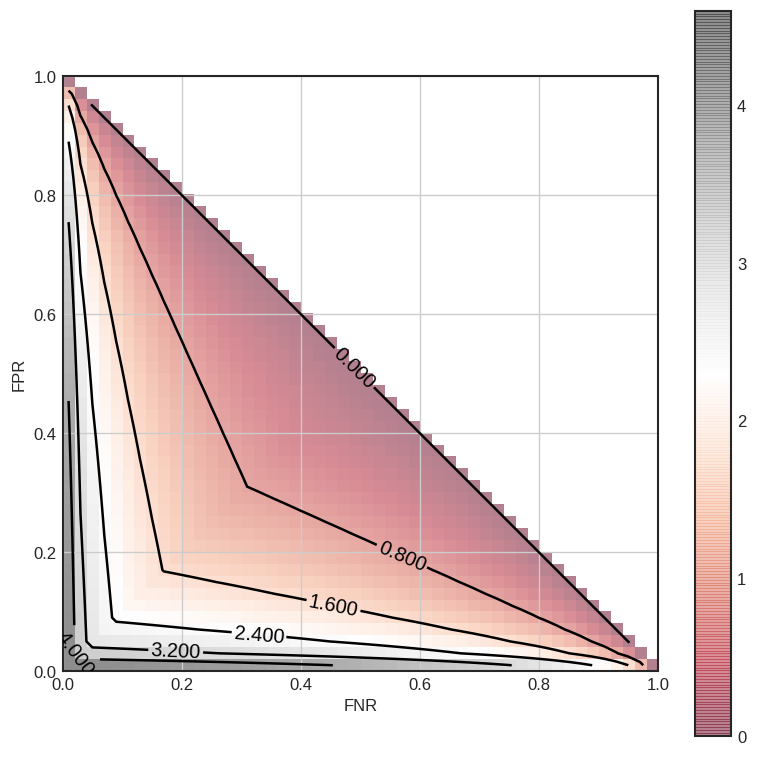

The seminal work of WassermanWasserman, Larry, and Shuheng Zhou. “A statistical framework for differential privacy.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 105.489 (2010): 375-389. and KairouzKairouz, Peter, Sewoong Oh, and Pramod Viswanath. “The composition theorem for differential privacy.” International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2015. shows how \(\epsilon\)-DP bounds these error rates. Specifically, for an \(\epsilon\)-DP algorithm:

\[FNR + e^\epsilon * FPR > 1\] \[FPR + e^\epsilon * FNR > 1\]These inequalities imply that an adversary cannot simultaneously keep both FPR and FNR low. In other words, \(\epsilon\) effectively limits how well an attacker can do, creating “trust regions”, which describe the performance of all adversaries. Plotting these regions for multiple values of epsilon, we get:

We observe how, as we increase \(\epsilon\), adversaries with lower (FNR, FPR) pairs are allowed for the mechanism, suggesting the existence of stronger adversaries, giving an interpretable alternative definition for \(\epsilon\). Next, we will give a similar interpretation to another well-known variant of differential privacy, Approximate Differential Privacy.

Approximate DP

Approximate DP is a relaxation of pure DP that introduces a parameter \(\delta\) to account for rare “catastrophic failure” events. This type of relaxation is common in cryptography to achieve practicality, as \(\epsilon\)-DP is both restrictive and hard on utility. Keeping the notation and above \((\epsilon, \delta)\)-DP is defined as:

.png)

Introducing \(\delta\) complicates the overall privacy guarantees, because it adds a second dimension to the analysis. Let’s reinterpret these guarantees through the lens of privacy profiles, which allows us to see how an attacker’s performance “trust region” grows once \(\delta\) is considered. Reusing the notation from before, an equivalent definition in terms of error rates is given by:

\[FNR + e^\epsilon * FPR > 1 - \delta\] \[FPR + e^\epsilon * FNR > 1 - \delta\]Similarly, plotting the above pair of inequalities for various pairs of \((\epsilon, \delta)\):

If you did not smile, then I recommend reading an introductory material on on Differential Privacy.

Observe how the gap between the blue dotted line and the \(\epsilon=0\) axis changes. When \(\delta = 0\), these lines coincide, matching the pure \(\epsilon\)-DP scenario. As \(\delta\) grows, a new “perfect privacy” zone emerges between the dotted line and the \(\epsilon = 0\) axis. In this zone, we essentially permit a tiny probability of unlikely adversarial behavior, hence the relaxation to Approximate DP. However, \(\delta\) must remain small so that these rare events don’t actually happen.

End Note

I think this is enough information for one sitting, we have a good basis for understanding how adversaries are bounded to performa against \(\epsilon\)-DP or \((\epsilon, \delta)\)-DP mechanisms. The defender doesn’t care about either the data or the attacker’s knowledge, our defence mechanism is a worst-case scenario one, good luck on breaking that!